Who wrote the national oath "India is my country, and All Indians are my brothers and sisters"?

"India is my country and all Indians are my brothers and sisters..." This famous national pledge recited by schoolchildren was composed in Visakhapatnam by then district treasury officer, Pydimarri Venkata Subba Rao, a native of Anneparthy village in Nalgonda, 50 years ago in 1962.

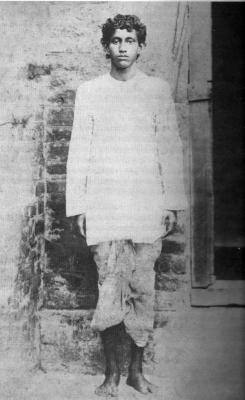

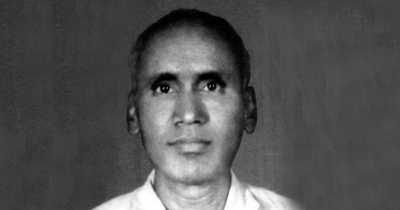

The Indian National Pledge was composed by Pydimarri Venkata Subba Rao. Subbarao, a noted author in Telugu and a bureaucrat, composed the pledge while serving as the District Treasury Officer of Visakhapatnam District in 1962. He presented it to the senior Congress leader Tenneti Viswanadam who forwarded it to the then Education Minister P.V.G. Raju. Subba Rao was born in Anneparti, Nalgonda District, Telangana. He was an expert in Telugu, Sanskrit, Hindi, English and Arabic languages. He worked as Treasury officer in the state of Hyderabad. After the formation of AP, He worked in Khammam, Nizamabad, Nellore, Visakhapatnam and Nalgonda Districts. The pledge was introduced in many schools in 1963.

The Indian National Pledge is commonly recited by Indians at public events, during daily assemblies in many Indian schools, and during the Independence Day and Republic Day commemoration ceremonies. Unlike the National Anthem or the National Song, whose authors are well known in India, P.V. Subba Rao, the author of the pledge remains largely a little-known figure, his name being mentioned neither in the books nor in any documents. Records with the Human Resources Development Ministry of the Government of India however record Subbarao as the author of the pledge. Subba Rao himself is thought to have been unaware of its status as the National Pledge with a position on par with the National Anthem and the National Song. Apparently, he came to know about this when his granddaughter was reading the pledge from her textbook.

Picture Credit : Google