Why can t we bounce radar signal off the sun and determine 1 au directly

On April 7, 1959, a three-member team led by Stanford electrical engineer Von R. Eshleman recorded the first distinguishable echo of a radar signal bounced off the sun. A.S.Ganesh tells you more about Eshleman and how his team achieved this success...

When we generally say "reach for the stars," we use it as a phrase to convey having high or ambitious aims. Some people, however, reach for the stars in the real sense. Stanford electrical engineer Von R. Eshleman was one of them and the star he reached out for was our sun.

Born into a farming community in Ohio, U.S. on September 17, 1924, Eshleman attended the General Motors Institute of Technology in Flint, Michigan, while still being a high school student. Similarly, even before earning his bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from George Washington University in 1949, he started attending Ohio State University.

Intrigued by wave science

Before this, he had a stint with the navy during World War II, working as an electrical technician from 1943-46. It was during this period that he was drawn towards wave science. Intrigued by both sonar and radar, Eshleman had the idea that he could bounce radio signals off the surfaces of the sun and the moon, in order to study their hidden structures. While his own ship-based experiments of the time weren't successful, they paved the way for his future research.

Having received his master's degree from Stanford in 1950, he went on to earn his Ph.D. in 1952. He was recruited by Stanford to be a research professor, a position he held until 1957, when he was promoted to the teaching faculty as an Assistant Professor (Associate Professor back then). By 1962, he had not only managed to bounce radar off the sun, but also became a full professor at Stanford.

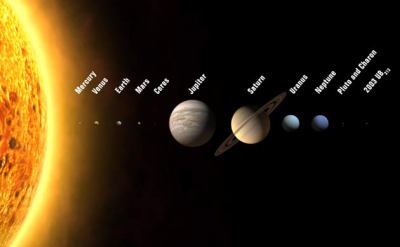

The same war that had planted the idea in Eshleman's mind for bouncing radar off surfaces also saw the rapid development of radar. Bouncing radar off distant surfaces wasn't an idea exclusive to Eshleman. Radar was successfully bounced off the moon in the 1940s itself and the first attempts to bounce radar off Venus were made in the late 1950s, albeit with mixed results.

16-minute round-trip

Eshleman's three-member team, including Lt. Col. Robert C. Barthle and Dr. Philip Gallagher, achieved success in bouncing radar off the sun on April 7, 1959. The tests, in fact, were run on April 7, 10 and 12, with an average time of 16 minutes and 32 seconds spent for the signals to travel the 149 million km distance between the Earth and the sun and back again.

The researchers needed many months to confirm that they had indeed succeeded and when they finally made their announcement public with a press conference in February 1960, it was with 99.999% certainty.

Coded pulse

Eshleman had explained to the gathered media persons that the radar antenna consisted of 5 miles of wire that was spread out across over 10 acres of land, and a 40,000 watt transformer.

Every time the test was conducted, a coded pulse was beamed at the sun in 30-second bursts. This was done to enable identification once it returned after bouncing off the sun.

While 40,000 watts were sent out, atmospheric and spatial dissipation meant that only about 100 watts reached the sun. Similar losses during the return journey meant that only a miniscule amount of energy returned, making detection difficult. The task was further complicated by the fact that this small amount of energy was now part of the vast amounts of similar energy that the sun itself radiates. The other wavelengths. By spending over six months with some of the best computers of the time, they were able to conclude that the coded pulse that they sent out was among the radio emissions of the sun.

In 1962, Eshleman, along with Stanford colleagues, founded the Stanford Center for Radar Astronomy to oversee radio experiments. Even though he began his career in radar astronomy, Eshleman is now best remembered for his pioneering work using spacecraft radio signals for precise measurements in planetary exploration. While he briefly served as Deputy Director of the Office of Technology Policy and Space Affairs in the U.S. Department of State, he was most comfortable among academic circles and hence returned to Stanford, where he flourished. Eshleman died in Palo Alto on September 22, 2017, five days after turning 93.

Picture Credit: Google