Zeus, king of the gods, is often shown with what weapon?

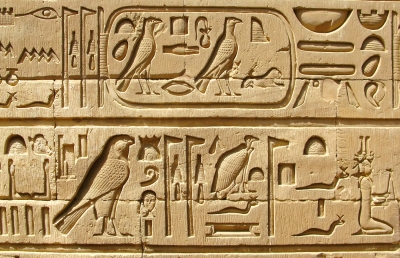

The ancients Greeks were polytheistic — that is, they worshipped many gods. Their major gods and goddesses lived at the top of Mount Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece, and myths described their lives and actions. In myths, gods often actively intervened in the day-to-day lives of humans. Myths were used to help explain the unknown and sometimes teach a lesson.

For example, Zeus, the king of the gods, carried his favorite weapon, the thunderbolt. When it rained and there was thunder and lightning, the ancient Greeks believed that Zeus was venting his anger.

Many stories about how the Greek gods behaved and interacted with humans are found in the works of Homer. He created two epic poems: the Iliad, which related the events of the Trojan War, and the Odyssey, which detailed the travels of the hero Odysseus. These two poems were passed down orally over many generations.

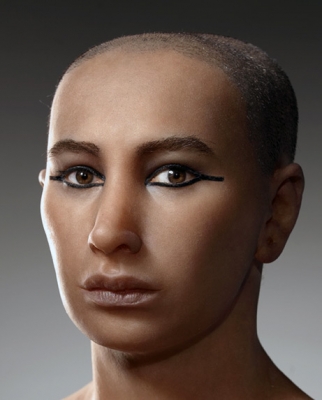

The Greeks created gods in the image of humans; that is, their gods had many human qualities even though they were gods. The gods constantly fought among themselves, behaved irrationally and unfairly, and were often jealous of each other. Zeus, the king of the gods, was rarely faithful to his wife Hera. Hera plotted against Zeus and punished his mistresses.

The Greek gods were highly emotional and behaved inconsistently and sometimes immorally. Greek religion did not have a standard set of morals, there were no Judaic Ten Commandments. The gods, heroes, and humans of Greek mythology were flawed.

In addition to Zeus and Hera, there were many other major and minor gods in the Greek religion. At her birth, Athena, the goddess of wisdom, sprang directly from the head of Zeus. Hermes, who had winged feet, was the messenger of the gods and could fly anywhere with great speed. Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was the most beautiful being in the universe. Her brother, Ares, the god of war, was sinister, mean, and disliked. Poseidon, ruled the sea from his underwater place and Apollo rode his chariot across the sky, bringing the sun with him.

Hades was in charge of the dead in the underworld. Almost all people went to Hades after they died whether they were good or bad. To get there, the dead had to cross the river Styx. Charon was the name of the boatman who ferried the souls of the dead across the river Styx to Hades.

Typically, the gods punished those who were bad. For example, Tantalus who killed his own son and served him to the gods for dinner was sent to Hades and made forever thirsty and hungry. Although there was a pool of clear, fresh drinking water at his feet, whenever Tantalus bent down to drink, the pool would dry up and disappear.

Likewise, over his head hung the most delicious fruit. However, whenever Tantalus reached for them, a wind would blow them just out of his reach. The English word "tantalize" derives from the name Tantalus.

Credit : UShistory.org

Picture Credit : Google