What are the oldest surviving photographs of moon?

In March 1840, English-born American John William Draper clicked what are now the oldest surviving photographs of the moon. Using the daguerreotype process that had just been invented, Draper clicked the photograph that showed lunar features.

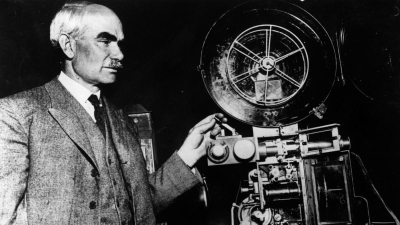

The smartphones in our hands these days are so powerful and equipped with great cameras that all we need to do to click a photograph of the moon is to wait for the moon to make its appearance and then take a photograph. It wasn't always this easy though. In fact, the oldest surviving photographs of the moon are less than 200 years old. The credit for taking those photographs goes to English-born American scientist, philosopher, physician, chemist, historian and photographer John William Draper.

Born in England in 1811, Draper went to the U.S. in 1832. After receiving a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania, he moved to New York University in 1837 and was one of the founders of NYU’s School of Medicine in 1840. He not only taught there for most of his life, but also served as the president of the med school for 23 years.

Learns Daguerre's process

His interest in medicine, however, didn't keep him away from dabbling with chemistry too. The chemistry of light-sensitive materials fascinated Draper and he learned about the daguerreotype process of photography after the news arrived in the U.S. from Europe. French artist and photographer Louis Daguerre had invented the process only in 1839.

Draper attempted to improve the photographic process of Daguerre and succeeded in ways to increase plate sensitivity and reduce exposure times. These advances not only allowed him to produce some of the best portrait photographs of the time, but also let him peer into the skies to try and capture the moon.

He met with failure in his first attempts over the winter of 1839-40. He tried to make daguerreotypes of the moon from his rooftop observatory at NYU, but like Daguerre before him, was unsuccessful. The images produced were either underexposed, or were mere blobs of light in a murky background at best.

Birth of astrophotography

By springtime in March 1840, however, Draper was successful, thereby becoming the first person ever to produce photographs of an astronomical object. He was confident enough to announce the birth of astrophotography to the New York Lyceum of Natural History, which later became the Academy of Sciences. On March 23, 1840, he informed them that he had created a focussed image of the moon.

The exact date when he first achieved it isn't very clear. While the photograph on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (which cannot be shown here due to rights restrictions) is believed to have been clicked on March 16 based on his laboratory notebook, the one pictured here was by most accounts on the night of March 26, three days after he had announced his success. The fact that many of Draper's original daguerreotypes were lost in an 1865 fire at NYU, and that daguerreotype photographs themselves don't have a long shelf life unless well-preserved from the moment they were taken means that the ones remaining become all the more significant.

The moon pictured here shows an extensively degraded plate with a vertically flipped last quarter moon, meaning the lunar south is near the top. This shows that Draper used a device called the heliostat to keep light from the moon focussed for a 20-minute-long exposure on the plate. They are of the same we and same circular image area as that of his first failed attempts.

Conflict thesis

Apart from being a physician and the first astrophotographer, Draper also has other claims to fame. He was the invited opening speaker in the famous 1860 meeting at Chford University where English naturalist Charles Darwin's ‘Origin of Species’ was the subject of discussion. He is also well known for his book ‘A History of the Conflict between Religion and Science’ which was published in 1874. This book marks the origin of what is known as the "conflict thesis” about the incompatibility of science and religion.

While we will probably never know on which particular March 1840 night Draper captured the first lunar image, his pioneering achievement set the ball rolling for astronomical photography. The fact that he achieved it with a handmade telescope attached to a wooden box with a plate coated with chemicals on the back makes it all the more remarkable.

Picture Credit : Google