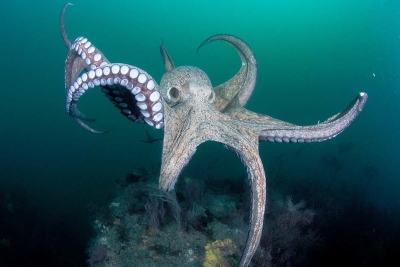

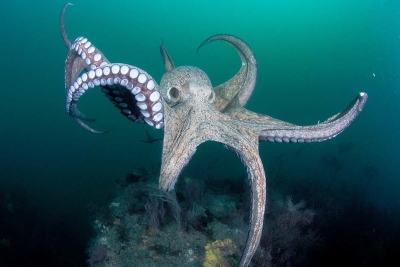

Octopuses have three hearts, which is partly a consequence of having blue blood. Their two peripheral hearts pump blood through the gills, where it picks up oxygen. A central heart then circulates the oxygenated blood to the rest of the body to provide energy for organs and muscles.

Octopuses are cephalopods, which literally means “head foot”, describing their truncated anatomy. Like the three other members of the group – squids, cuttlefish and nautiluses – they have blue blood, because it uses a copper-rich protein to transport oxygen. This helps explain why they need three hearts.

Our red blood gets its colour from an iron-based protein called haemoglobin, which is carried in red blood cells. Cephalopods use a copper-based protein called haemocyanin, which is much larger and circulates in the blood plasma. Haemocyanin is less efficient at binding with oxygen than is haemoglobin. However, octopuses compensate for this by having three hearts – two “branchial” hearts, which receive deoxygenated blood from around the body and pump it through the gills, and one “systemic” heart, which takes that oxygen-rich blood, increases its pressure and then circulates it around the rest of the body.

One clue that the three-heart system is needed to help power an octopus’s active lifestyle comes from the other cephalopods. The only member of the group not to share this anatomical anomaly is the nautilus, which is more sedentary and energy-efficient than the others. What’s more, octopuses may be particularly reliant on good circulation of oxygenated blood to power their extensive nervous system. Octopuses have nine brains: a central brain between their eyes and a mini one in each arm. This brain tissue is notoriously fuel intensive.

Of course, octopuses also need oxygen to power their muscles. Their preferred mode of locomotion is to crawl along the seabed. They can also swim at high speeds, propelled by jets of water, which they shoot out of a tube called a siphon. However, when they are swimming, the systemic heart does not beat, so they tire easily.

There are some 300 species of octopus, ranging in size from the giant Pacific octopus, which can weigh 50 kilograms, to the tiny Octopus wolfi, at less than a gram.

Almost all octopuses are solitary. They live in a wide range of habitats from intertidal zones to deep water, and this is where having blue blood may be advantageous. Haemocyanin seems to help octopuses transport oxygen efficiently in environments that vary widely in temperature and oxygen levels. It is particularly efficient in the cold ocean, which is a boon for species like the Antarctic octopus. However, haemocyanin loses its ability to bind to oxygen as acidity increases. That doesn’t bode well for octopuses as climate change makes oceans warmer and more acidic.

Credit : New Scientist

Picture Credit : Google