What is the Gilgamesh dream tablet?

A 3,500-year-old tablet featuring the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh was returned to Iraq recently, three decades after its disappearance. The clay tablet features characters in cuneiform, one of the oldest forms of writing known. It is believed to have been stolen from an Iraqi museum in 1991 while the country was caught up in the first Gulf War, says AFP. The Epic of Gilgamesh is considered one of the oldest pieces of literature in the world, telling the story of a Mesopotamian king on a quest for immortality.

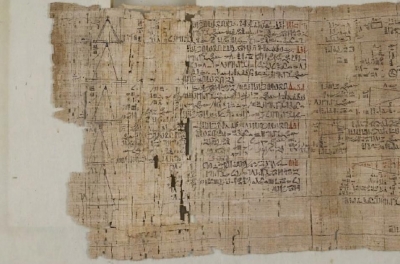

The tablet contains a portion of the Epic of Gilgamesh written in the Akkadian language in cuneiform script - a system of writing on clay used in ancient Mesopotamia.

Scholars discovered the epic in 1853, when a 12-tablet version was found in the ruins of the library of an Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, in northern Iraq.

The events revolve around King Gilgamesh of Uruk - an area corresponding to southern Iraq. The myth is based on a real king who ruled sometime between 2,800 and 2,500 BC.

The Dream tablet recounts a part of the epic in which King Gilgamesh describes his dreams to his mother, who interprets them as announcing the arrival of a new friend, who will become his companion.

Little is known about what happened to the tablet between 1991 and 2003, when it was bought by an antiques dealer in London. The dealer shipped the tablet to the US by international post without declaring formal entry.

In 2007, the dealer sold the tablet to another buyer with a false letter stating that it had been inside a box of ancient bronze fragments purchased in 1981.

It was sold again several times at auction in different countries before being bought in 2014 in a private sale by Hobby Lobby, an arts and crafts firm with a conservative Christian ethos. The company paid more than $1.67m (£1.2m) for the tablet, which was prominently displayed in its Museum of the Bible.

Doubts emerged over the tablet's provenance in 2017, when a curator at the museum sought more information about where it came from. The museum also informed the Iraqi government that the item was in its possession.

Credit : BBC News

Picture Credit : Google