What started the rumour that the moons of Mars may be artificial satellites, like space stations orbiting the Earth?

There are two reasons why people started believing that Martian moons may be artificial satellites. One was a scientific theory and the other, an April Fool’s day joke!

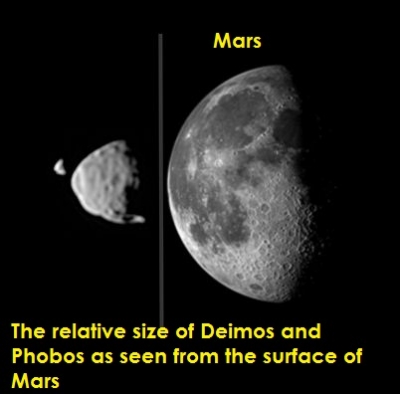

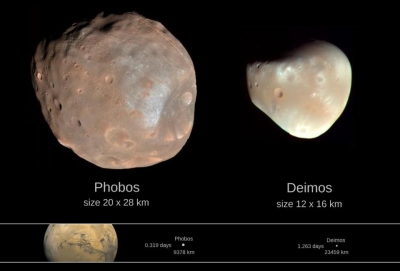

Astronomers and scientists observing Phobos in the late 1950s saw that the moon was slowly spiralling closer and closer to Mars. Back then, they did not have enough information to understand why Phobos was behaving this way. A famous Russian astrophysicist named losif Shklovsky came up with a possible explanation - if Phobos was capable of getting slowed down by Mars’ thin atmosphere, and then it should be having a very low density, meaning it might be hollow, and may even be an artificial satellite! The U.S. President’s scientific advisor at the time, Fred Singer, too seemed to support this argument, while also raising doubts about the accuracy of the measurements the theory was based on. But the “if’s” and “might be’s” in their statements were ignored by a few who were fascinated by the possibility of Phobos being the evidence of extra-terrestrial life on Mars!

At around the same time, an American space enthusiast and columnist, Walter Houston, published an article in the April Fool’s edition of a magazine. He wrote that the moons of Mars were actually space stations made by a group of super-intelligent Martians! Even though this was meant to be a joke, it soon became “viral!”

Picture Credit : Google