Did Mars have liquid water in the past?

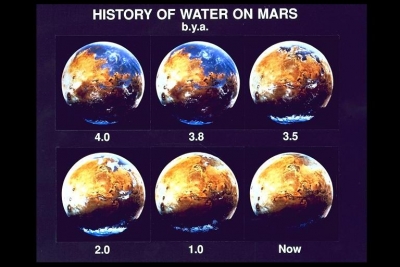

Looking at the photographs of the dry and dusty Mars, would you believe that billions of years ago the planet had enough water to cover about one-fifth of its surface? Scientists say that the Red Planet once used to have rivers, lakes and vast oceans as well! Back then, Mars may have had a thicker atmosphere which made it a warmer and wetter planet than it is today.

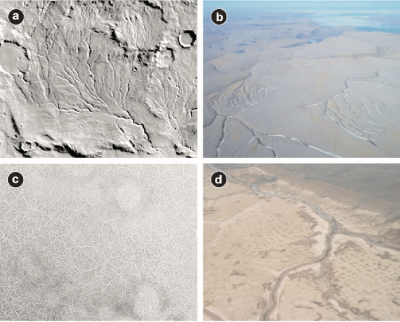

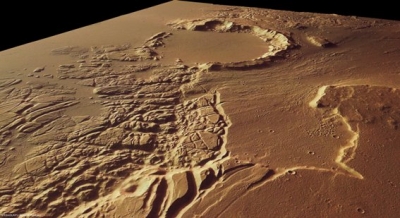

Evidence of Mars’ “watery” past can be found on its surface itself. Certain minerals found in Martian rocks could have formed only in places where water was present. The Martian outflow channels and valley networks point to a time when liquid water used to flood or flow across the Martian surface. Lake beds with tell-tale delta formations have also been reported. Even Martian meteorites found on the Earth show that they were exposed to water on their parent planet!

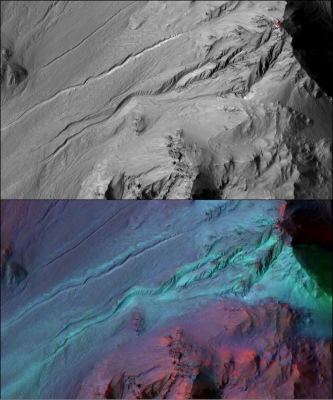

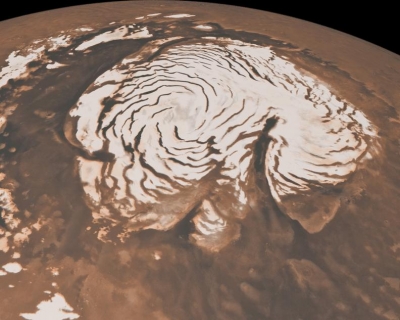

Today, the thin atmosphere of Mars would cause any liquid water on the surface to evaporate. But still water exists in the frozen form as polar ice caps, and potentially beneath the Martian surface. Scientists have also found dark streaks on steep slopes, called Recurring Slope Lineae, or RSL, that were believed to be a mixture of soil and highly concentrated salt water flowing down the Martian slopes. (But some scientists argue that they may just be streams of sand and dust.)

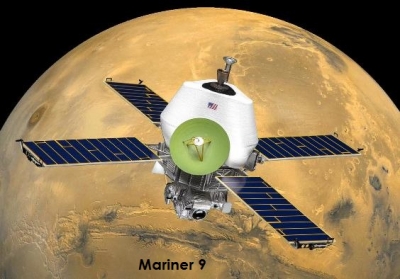

Picture Credit : Google