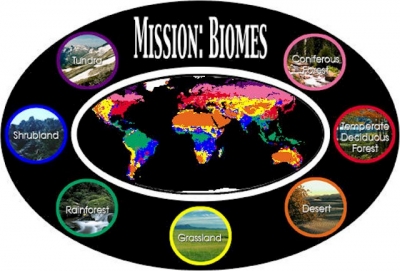

What are Biomes? What are the types of Biomes?

Earth can be divided up into a number of different types of landscape. These zones are called biomes. Every biome is home to a particular group of plants and animals that are suited to the conditions found there.

A biome is different from an ecosystem. An ecosystem is the interaction of living and nonliving things in an environment. A biome is a specific geographic area notable for the species living there. A biome can be made up of many ecosystems. For example, an aquatic biome can contain ecosystems such as coral reefs and kelp forests.

Mountains

Mountains are high places with a cold, windy climate. It gets colder the higher up you go, so different groups of plants and animals are found at different heights. Winds are another factor that make mountain biomes different from the areas around them. By nature of their topography, mountains stand in the path of winds. Winds can bring with them precipitation and erratic weather changes.

That means that the climate on the windward side of a mountain (facing the wind,) will likely be different from that of the leeward side (sheltered from the wind.) The windward side of a mountain will be cooler and have more precipitation, while the leeward side will be drier and warmer.

Deserts

Deserts are very dry, as there is little or no rainfall. They can be very hot or very cold. The plants and animals found in deserts have adapted to living in these extreme conditions. Due to the availability of little moisture in the air to capture and hold on to the heat emanating from the high temperatures during the day, desert nights are typically cold. A combination of extreme temperature fluctuations and incredibly low levels of water makes the desert biome a very harsh land mass to live in.

Temperatures are so extreme during the day because there is very little moisture in the atmosphere to block out the sun’s rays. This means that the sun’s energy is absorbed on the ground surface. The ground surface then heats up the surrounding air.

Wetlands

Wetlands are permanently flooded with water. This can be salt water, fresh water, or a mixture of both. Swamps, bogs, marshes, and deltas are all types of wetlands. Many birds thrive in this environment. Plant matter is released into freshwater biomes from a wetland biome. The importance of this is that it allows for fish to have plenty of types of food for them to survive. Florida has one of the largest wetland biomes in the world. The humid conditions are perfect for such forms of plant and animal life to be able to survive.

Rainforests

Rainforests get a lot of rain. Most of then also get a lot of sunlight, and are very hot all year round. They are home to many different plants and animals. The largest rainforest is the tropical Amazon rainforest in South America.

Rainforest plants have made many adaptations to their environment. With over 80 inches of rain per year, plants have made adaptations that helps them shed water off their leaves quickly so the branches don't get weighed down and break. Many plants have drip tips and grooved leaves, and some leaves have oily coatings to shed water.

Many species of animal life can be found in the rain forest. Common characteristics found among mammals and birds (and reptiles and amphibians, too) include adaptations to a life in the trees, such as the prehensile tails of New World monkeys. Other characteristics are bright colors and sharp patterns, loud vocalizations, and diets heavy on fruits.

Insects make up the largest single group of animals that live in tropical forests. They include brightly colored butterflies, mosquitoes, camouflaged stick insects, and huge colonies of ants.

Deciduous forests

The temperature and rainfall in deciduous forests changes from season to season. During the autumn and winter, most trees change colour and lose their leaves. The animals adapt to the climate by hibernating in the winter and living off the land in the other three seasons. The animals have adapted to the land by trying the plants in the forest to see if they are good to eat for a good supply of food. Also the trees provide shelter for them. Animal use the trees for food and a water sources. Most of the animals are camouflaged to look like the ground.

The plants have adapted to the forests by leaning toward the sun. Soaking up the nutrients in the ground is also a way of adaptation.

Coniferous forests

These forests have long, cold, snowy winters and short, warm summers. Trees here have adapted to this harsh climate. They are mostly evergreen, meaning they stay green all year round. Precipitation is significantly high in coniferous forest biomes. The average annual precipitation in coniferous rain forest biomes ranges from 300 to 900 mm. A few temperate coniferous forests get more than 2000 mm of rain annually. The total amount of precipitation received in this biome hinges on its location. For instance, in northern coniferous forests, winters tend to be lengthy, cold and relatively dry, whereas the short summers tend to be moderately warm and moist. In areas of lower latitudes, precipitation tends to be equally spread out all year round. During winter months, precipitation falls as snow, while in the summer, it falls as rain.

Grasslands

Grasslands get little rainfall only grass and a few small trees and bushes can grow in these dry places. But many animals, such as zebras and elephants, manage to live there. There is a large area of grassland that stretch from the Ukraine of Russia all the way to Siberia. This is a very cold and dry climate because there is no nearby ocean to get moisture from. Winds from the arctic aren't blocked by any mountains either. These are known as the Russian and Asian steppes.

In the winter, grassland temperatures can be as low as -40° F, and in the summer it can be as high 70° F. There are two real seasons: a growing season and a dormant season. The growing season is when there is no frost and plants can grow (which lasts from 100 to 175 days). During the dormant (not growing) season nothing can grow because its too cold.

Tundra

It is usually very cold and windy in the tundra, and there is not much rain. The ground is often covered in snow, so only a few plants and animals can live there. Mountain goats, sheep, marmots, and birds live in mountain—or alpine—tundra and feed on the low-lying plants and insects. Hardy flora like cushion plants survive in the mountain zones by growing in rock depressions, where it is warmer and they are sheltered from the wind. The Arctic tundra, where the average temperature is -30 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit (-34 to -6 degrees Celsius), supports a variety of animal species, including Arctic foxes, polar bears, gray wolves, caribou, snow geese, and musk oxen. The summer growing season is just 50 to 60 days, when the sun shines up to 24 hours a day.

Polar ice

This is the coldest biome on Earth. The freezing temperatures make it difficult for any plants to survive. During the summer, the sun could shine for 24 hours per day and the temperature would still not go over 0 degrees Celsius. In the winter, the opposite occurs; there is no sunshine whatsoever during the winter and as a result, the temperatures will go even lower than usual. Animals, such as polar bears, penguins, and seals, have adapted well to life here. One of the most recognizable feature of a polar ice biome is the presence of permanent ice. As a result, no vegetation can grow here except for some microscopic algae.

Picture Credit : Google