In which year did Christiane Nusslein-Volhard win a Nobel?

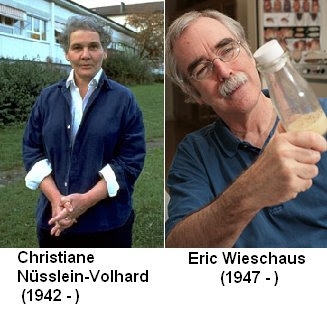

Christiane Nusslein-Volhard, (born October 20, 1942, Magdeburg, Germany), German developmental geneticist who was jointly awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with geneticists Eric F. Wieschaus and Edward B. Lewis for their research concerning the mechanisms of early embryonic development.

In the early 1990s Nusslein-Volhard began studying genes that control development in the zebra fish Danio rerio. These organisms are ideal models for investigations into developmental biology because they have clear embryos, have a rapid rate of reproduction, and are closely related to other vertebrates. Nusslein-Volhard studied the migration of cells from their sites of origin to their sites of destination within zebra fish embryos. Her investigations in zebra fish have helped elucidate genes and other cellular substances involved in human development and in the regulation of normal human physiology.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Nusslein-Volhard received the Leibniz Prize (1986) and the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award (1991). She also published several books, including Zebrafish: A Practical Approach (2002; written with Ralf Dahm) and Coming to Life: How Genes Drive Development (2006).

Credit : Britannica

Picture Credit : Google