|

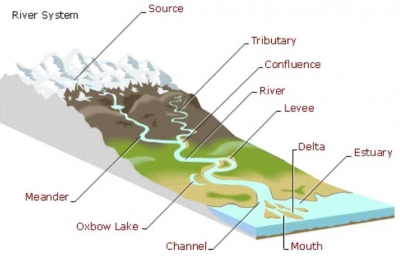

As a river reaches the sea or a lake and slows down, sediment- sand, silt and mud – builds up at its mouth, blocking its flow. The river then breaks up into several individual strands of water that make their way to the larger water body. The Nile forms a classic delta formation as the river enters into the Mediterranean Sea.

|

One of the first texts to describe deltas was History, written during the 5th century BCE by Greek historian Herodotus. In that work, Herodotus mentioned that the Ionian people used the term delta to describe the low-lying region of the Nile River in Egypt. During a visit to the region, Herodotus also recognized that the land bounded by the seaward-diverging distributary branches of the Nile and the sea was deltoid in shape; he is often given credit for first using the Greek letter ? (delta) to describe it. Although many of the world’s deltas are deltoid, or triangular, in shape, notable exceptions exist. In most cases, the delta shape is controlled by the outline of the water body being filled by sediments. For this reason, the term delta is now normally applied, without reference to shape, to the exposed and submerged plain formed by a river at its mouth.

Deltas have been important to humankind since prehistoric times. Sands, silts, and clays deposited by floodwaters were extremely productive agriculturally; and major civilizations flourished in the deltaic plains of the Nile and Tigris-Euphrates rivers. In recent years geologists have discovered that much of the world’s petroleum resources are found in ancient deltaic rocks.

Deltas display much variation in size, structure, composition, and origin. These differences result from sediment deposition taking place in a wide range of settings. Numerous factors influence the character of a delta, the most important of which are: climatic conditions, geologic setting and sediment sources in the drainage basin, tectonic stability, river slope and flooding characteristics, intensities of depositional and erosional processes, and tidal range and offshore energy conditions. Combinations of these factors and time give rise to the wide variety of modern deltas. The presence of a delta represents the continuing ability of rivers to deposit stream-borne sediments more rapidly than they can be removed by waves and ocean currents. Deltas typically consist of three components. The most landward section is called the upper delta plain, the middle one the lower delta plain, and the third the subaqueous delta, which lies seaward of the shoreline and forms below sea level.

Credit: Britannica

Picture Credit : Google