WHAT IS RESEARCH OF MAKING CEMENT FROM FOOD WASTE BY JAPANEES?

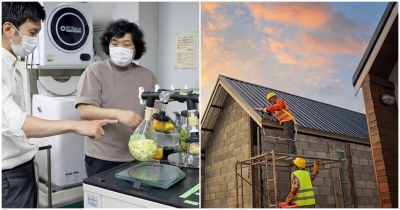

Food waste is a huge problem worldwide. In Japan alone, the edible food waste produced in 2019 amounts to 5.7 million tons. While their government aims to reduce that to around 2.7 million tons by 2030, there are others who are working on the same problem differently. Researchers from Tokyo University, for instance, have found a new method to create cement from food waste.

In addition to addressing the issue of food waste, the researchers also hope to reduce global warming in this way. Apart from the estimate that cement production accounts for 8% of the world's carbon dioxide emissions, there is also the fact that wasted food materials rotting in landfills emit methane. By using these materials to make cement, scientists hope to reduce global warming.

The researchers borrowed a heat pressing concept that they had employed to pulverise wood particles to make concrete. By using simple mixers and compressors that they could buy online, the researchers used a three-step process of drying. pulverising, and compressing to turn wood particles into concrete.

Heat pressing concept

Following this success, they decided to do the same to food waste. Months of failures followed as they tried to get the cement to bind by tuning the temperature and pressure. The researchers say that this was the toughest part of the process as different food stuff requires different temperatures and pressure levels.

The researchers were able to make cement using tea leaves, coffee grounds, Chinese cabbage, orange and onion peels, and even lunch-box leftovers. To make this cement waterproof and protect it from being eaten by rodents and other pests, the scientists suggest coatings of lacquer.

Cement that can be eaten!

Additionally, the researchers tweaked flavours with different spices to arrive at different colours, scents, and taste of the cement. Yes, you read that right. This material can even be eaten by breaking it into pieces and then boiling it.

The scientists hope that their material can be used to make edible makeshift housing materials for starters, as they are bound to be useful in times of disasters. If food cannot be delivered to evacuees, for instance, then they could maybe eat makeshift beds prepared from food cement. The food cement that they have created is reusable e and biodegradable.

Picture Credit : Google