Are spiders insects?

Technically speaking, spiders are not insects! Why aren’t they exactly? We’ll look into a few main reasons why spiders and insects are so different. But first, let’s break down what spiders and insects have in common, which is actually quite a bit.

To understand the similarities and differences between spiders and insects, we have to cover a bit of taxonomy. Taxonomy is the science of classifying all living things. Spiders, insects, fish, birds, and humans all fall into the Kingdom Animalia. Pretty much every animal is able to breathe and move, unlike plants and fungi. Additionally, animals are multicellular, unlike bacteria. Let’s dive deeper into the world of taxonomy and discover more about the classification of spiders and insects.

The next taxonomic level down is where spiders and insects lose their similarities. Spiders are in a class of animals known as arachnids. Spiders, scorpions, mites, and ticks are all different kinds of arachnids. Perhaps the biggest difference between arachnids and insects are the number of legs they have. One of the defining characteristics of spiders and other arachnids is that they have 8 legs. Insects, on the other hand, only have 6. This difference may not seem that significant, but it’s one of the most important things that separate these two classes of animals!

Next up is the number of body segments. Spiders have two segments – the abdomen, and the cephalothorax (which is a combination of a head and thorax). Insects boast three distinct segments – an abdomen, a thorax, and a head. Although they serve essentially the same functions, the body segments are another characteristic that spiders and insects do not have in common.

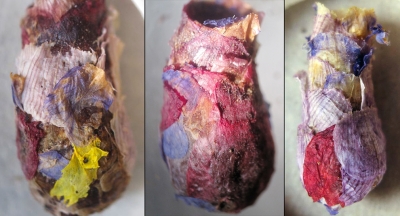

Picture Credit : Google