Who was the first person to float freely in space?

Images from space that show earth as nothing more than a blur of blue tug at our hearts in a way that can’t be put into words. The ones that you see here, while evoking such emotions, are also iconic in their own right. This is because they show the first human ever to walk untethered in space. The subject of these photographs is NASA astronaut Bruce McCandless II.

Born in Boston in 1937, McCandless did his schooling at Long Beach, California and received his Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy in 1958. He then obtained his Master of Science degree in Electrical Engineering from Stanford University in 1965, and eventually also ended up with a Masters in Business Administration from the University of Houston in 1987.

Communicator role

A retired U.S. Navy captain, McCandless was one of 19 astronauts selected by NASA in April 1966. He served as the mission control communicator for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin during their famous 1969 Apollo 11 mission, which included the first human landing on the moon. McCandless, in fact, famously felt let down by Armstrong as the latter hadn’t revealed ahead what he had planned to say while setting foot on the moon.

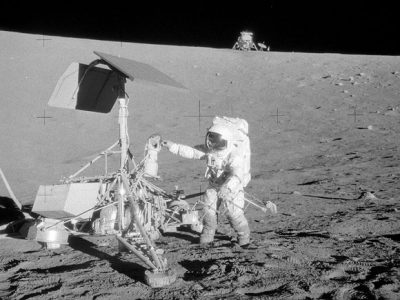

McCandless flew as the mission specialist on two space shuttles, STS-41B in 1984 and STS-31 in 1990. While the 1984 mission saw him become the first human to perform an untethered spacewalk, he helped deploy the Hubble Space Telescope during the 1990 mission.

Helps develop MMU

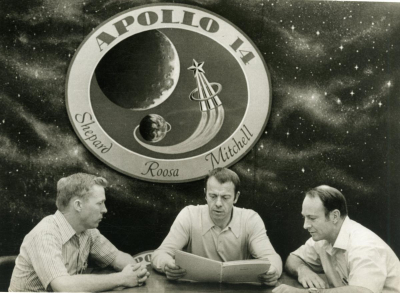

Apart from these, McCandless also served as a member of the astronaut support crew for the Apollo 14 mission and was a backup pilot for the first crewed Skylab mission. For the M-509 astronaut manoeuvring experiment that was flown in the Skylab programme, McCandless was a co-investigator. He collaborated on the development and helped design what came to be known as the MMU – manned manoeuvring unit.

The STS-41B was launched on February 3, 1984. Four days later, on February 7, McCandless stepped out of the space shuttle Challenger into nothingness. As he moved away from the spacecraft, he floated freely without any earthly anchor.

"Heck of a big leap for me"

“It may have been a small step for Neil, but it’s a heck of a big leap for me,” were McCandless’ first words. If the mood at mission control had been apprehensive before, the raucous laughter that followed this comment certainly reduced the tension - a fact that was confirmed by his wife, who was also at mission control. McCandless would later say that his comment was consciously thought out and that it was his way of saying things were going okay, apart from getting back at Armstrong for not revealing his words in 1969.

The images that were shot then, showing McCandless spacewalking without tethers, gained widespread fame. The spacewalk was the first time the MMU that he helped develop was used. These nitrogen-propelled, hand-controlled devices afforded much greater mobility to their users as opposed to restrictive tethers used by previous spacewalkers.

Fellow astronaut Robert L. Stewart later tried out the MMU that McCandless first used. Two days later, both of them tried another similar unit with success. By February 11, the STS-41B mission was complete as the Challenger safely landed at NASA’s Kennedy Space Centre.

In one of his last interviews, before his death in December 2017, McCandless told National Geographic what he had probably told countless others who wanted to know how it was out there.

Fun, but cold

While he always maintained that it was fun, he also adds that the single thing that disturbed him as he moved away from the shuttle was that he got extremely cold, with shivers and chattering teeth.

The reason for that is pretty straightforward. While he had prepared for that moment for years, he wasn’t prepared for the temperature in the suit. As the suit was designed to keep astronauts comfortable while working hard in a warm environment, even the H (hot) position on the life support system actually provided minimal cooling. Considering that McCandless wasn’t really performing strenuous labour during the first hours of his untethered spacewalk, he felt cold. That’s a small price to pay for becoming the first-ever human to walk freely in space.

Picture Credit : Google